Publication in Nature

A team of researchers from Utrecht and Zürich have developed a new method for the production of wavy surfaces with nanometre precision. In the future this method could be used, for instance, to make more efficient and compact optical components for data transmission. The researchers are publishing their results today in Nature. Utrecht researchers Freddy Rabouw and Sander Vonk were responsible for the design and analysis of the surfaces. Rabouw joined the research team while working at ETH Zürich as an NWO Rubicon fellow, while Vonk visited the group as an internship for his double Master’s degree in Nanomaterials and Experimental Physics.

Many optical applications, such as data transmission via optical fibres, use diffraction gratings, which deflect light of different colours in precisely determined directions. For decades, scientists have been trying to improve the design and production of diffraction gratings to make them suitable for today’s demanding applications. The team of researchers from Zürich and Utrecht, together with private company Heidelberg Instruments Nano, have now developed a completely new method by which more efficient and more precise diffraction gratings can be produced.

Smooth nano-ripples

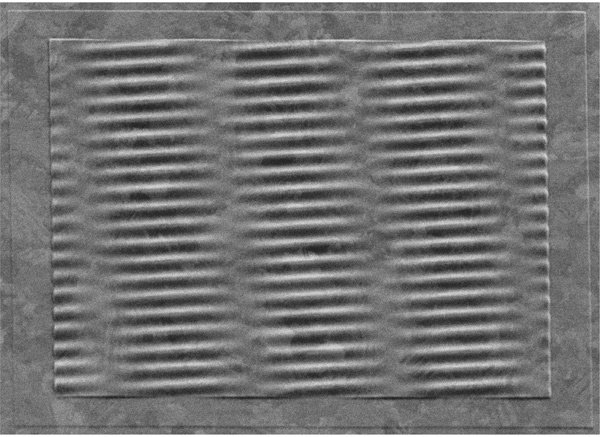

For a diffraction grating to work properly its grooves need to have a separation similar to the wavelength of the light, which is around one micrometre – a hundred times smaller than the width of a human hair. Currently, those grooves are etched using manufacturing techniques from the microelectronics industry, explains Nolan Lassaline, first author of the study. “This means, however, that the grooves of the grating are rather square in shape. However, physics tells us that grooves with a smooth and wavy pattern, like ripples on a lake, would steer light more efficiently.”

Hot probe

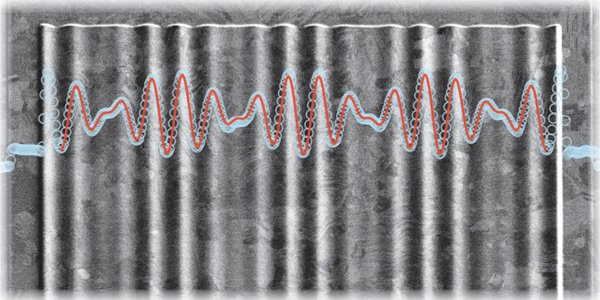

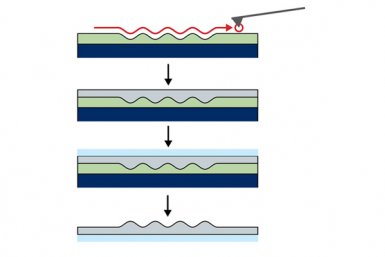

The researchers were able to develop such smooth and wavy nano-ripples with a technique based on the scanning tunnelling microscope, which scans material surfaces with a sharp probe with high resolution. The researchers heat the tip of the scanning probe to almost 1000 degrees Celsius and press it into a polymer surface at certain locations. This causes the molecules of the polymer to break up and evaporate at those locations, allowing the surface to be precisely sculpted. Then, the pattern is transferred to an optical material by depositing a silver layer onto the polymer. The silver layer can then be detached from the polymer and used as a reflective diffraction grating.

Practically perfect

“This allows us to produce arbitrarily shaped diffraction gratings with a precision of just a few atomic distances in the silver layer,” says research leader Prof. David Norris. Unlike traditional square-shaped grooves, such gratings are no longer approximations of an ideal surface, but practically perfect and can be shaped in such a way that the interference of the reflected light waves create precisely controllable patterns.

Such perfect gratings enable new possibilities for controlling light. This means they have a range of possible applications, such as more efficient fiber optics for data transmission, ultrathin camera lenses, and compact holograms with sharper images. The new technique promises a broad impact in optical technologies such as futuristic smartphone cameras, biosensors, or autonomous vision for robots and self-driving cars.

Publication

Optical Fourier surfaces external link

N. Lassaline, R. Brechbühler, S.J.W. Vonk*, K. Ridderbeek, M. Spieser, S. Bisig, B. le Feber, F.T. Rabouw*, D.J. Norris

Nature 2020, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2390-x

* researchers affiliated with Utrecht University

Source: website Utrecht University